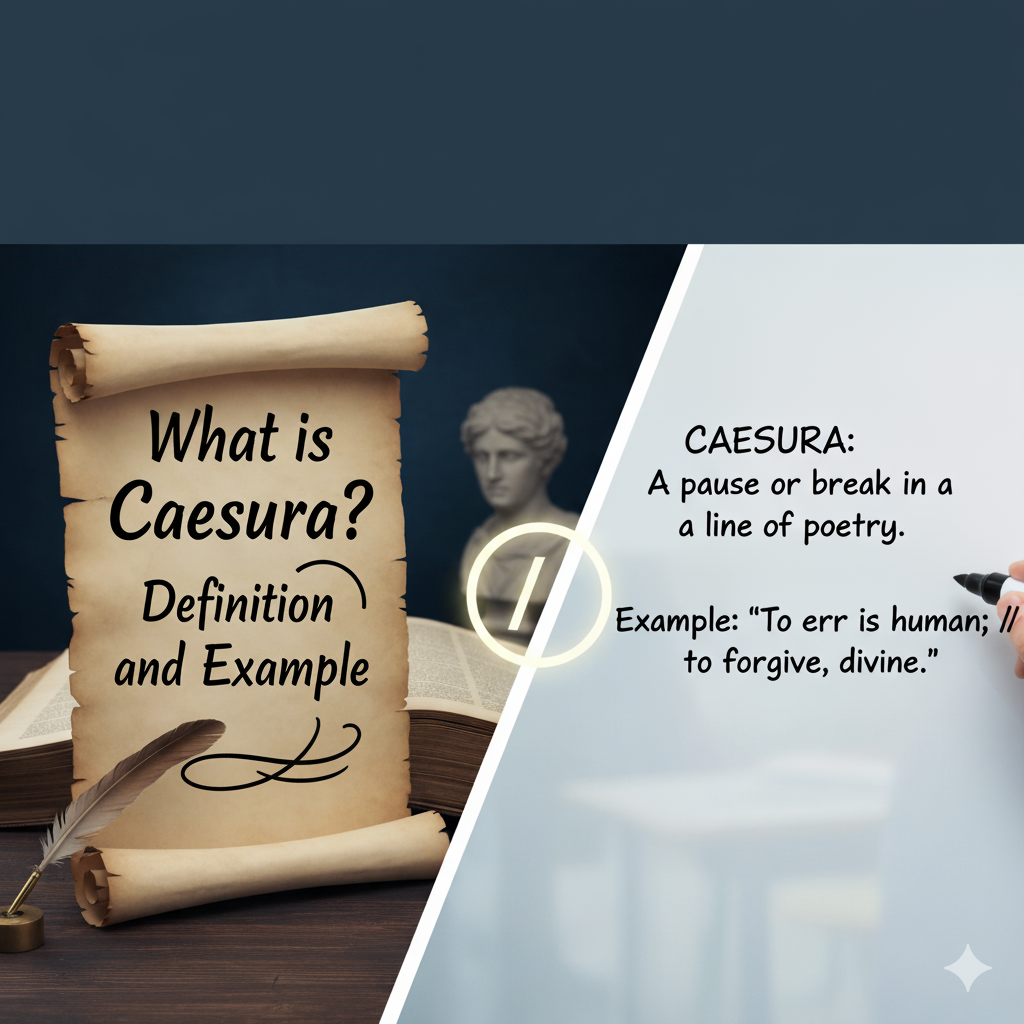

What is Caesura; Definition and Example

Caesura is a break or pause in a line of poetry, dictated by the natural rhythm of the language and/or enforced by punctuation.

A line may have more than one caesura, or none at all. If a Caesura is near the beginning of the line, it is called the initial caesura; near the middle, medial; near the end, terminal. The commonest is medial. An accented (or masculine) caesura follows an accented syllable, and an unaccented (or feminine) caesura follows an unaccented syllable.

In OE verse, the caesura was used rather monotonously to indicate the half-line:

Đa waes on burgum || Beowulf Scyldinga

leof leodcyning || longe þrage.

Another famous example is from William Langland’s Piers Plowman

Loue is leche of lyf || and nexte owre lorde selue,

And also þe graith gate || þat goth in-to heuene.

The development of the iambic pentameter in Geoffrey Chaucer’s hands produced much more subtle varieties:

With him ther was his sone, || a yong Squier

A lovyere || and a lusty bacheler,

With lokkes crulle || as they were leyd in presse. (Prologue to the Canterbury Tales)

Blank verse allowed an even wider range in the preservation of speech rhythms, as these lines from Shakespeare’s King Henry VIII suggest:

I have ventur’d

Like little wanton boys || that swim on bladdrs,

This many summers || in a sea of glory;

But far beyond my depth. || My high-blown pride

At length broke under me, || and now has left me,

Weary and old with service, || to the mercy

Of a rude stream || that must for ever hide me.

In more modern verse there is a great deal of variation in the placing of the caesura, as can be seen in the work of outstanding innovators like Gerard Manley Hopkins, W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, and T. S. Eliot. One famous example is from Yeats:

That is no country for old men. || The young

In one another’s arms, || birds in the trees

– Those dying generations – || at their song,

The salmon-falls, || the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, || commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, || born, || and dies.

Caught in that sensual music || all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect. (Sailing to Byzantium)

The caesura, then, not only regulates rhythm but also acts as a powerful expressive device, shaping meaning as much as sound. In narrative poetry, a well-placed pause often dramatizes a moment of tension, hesitation, or revelation, as if the silence itself were part of the storytelling. In lyric poetry, the caesura can mimic natural speech rhythms or the sudden break of thought, giving verse an intimacy and immediacy that strict metrical flow might otherwise suppress.

Modern poets in particular have used caesura to capture fragmented consciousness, hesitation, or conflict. T. S. Eliot, for instance, deploys pauses in “The Waste Land” to mirror the disjointed, collage-like experience of modernity, where voices shift and thoughts fracture. Similarly, Sylvia Plath uses abrupt breaks in Daddy to give her lines a breathless, halting intensity, reflecting the speaker’s volatile emotions. The caesura, in such contexts, is no longer a mere metrical convention but a psychological and dramatic force.

Critics have often pointed out that the caesura embodies the paradox of poetry: it is a silence that speaks. As George Saintsbury remarks in his History of English Prosody, the caesura “is not so much a gap in the verse as the hidden articulation of its pulse,” a feature that animates both metrical order and expressive freedom. In this sense, the caesura becomes a hinge between structure and spontaneity, tradition and innovation.

Thus, from the rigid half-line breaks of Beowulf to the free, shifting pauses of Yeats and Eliot, the caesura has remained a central instrument of poetic craft. Its function may vary—sometimes stylizing, sometimes humanizing—but its presence reminds us that poetry is as much about silence and breath as it is about sound and words.