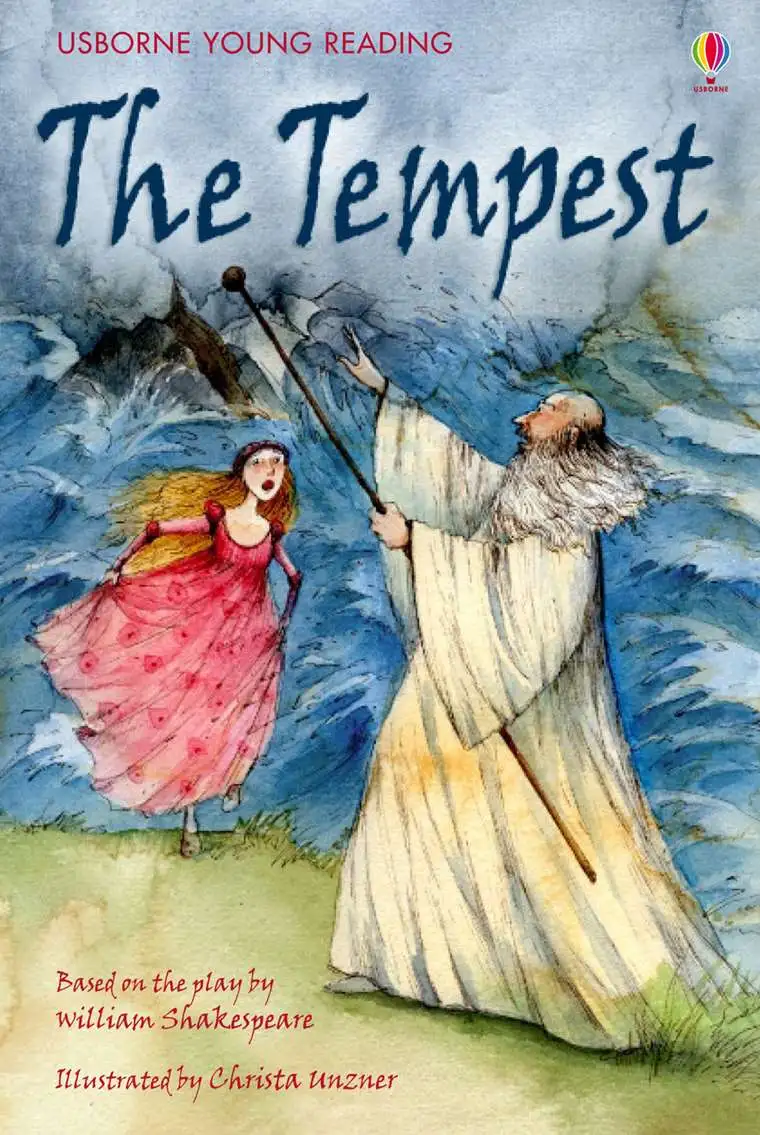

Significance of the Comic Subplot of Shakespeare’s play “The Tempest”

The comic underplot of The Tempest is introduced in the second scene of the second Act. It concerns the conspiracy of Caliban and his drunken associates, Stephano and Trinculo, against Prospero’s life and their attempt to seize possession of the island, with Stephano to be king and the other two to be his viceroys. Caliban enters with a burden of wood and curses Prospero for tormenting him in various ways. Presently, Trinculo comes there, and in his fright, Caliban takes him to be one of the spirits of Prospero come to torment him and falls flat upon the ground to escape his notice. Trinculo takes Caliban at first for a fish, then for a monster, and lastly as an islander knocked down by thunder. The storm soon bursts, and Trinculo takes shelter under the gaberdine of Caliban. Stephano now enters in a drunken state and takes the two jumbled together as some queer monster of the island. Recognition soon follows, and the two, with Caliban, who is won over by his ‘heavenly liquor’, conspire against Prospero. Prospero is to be murdered during his afternoon sleep. Stephano is to be king, with Miranda as queen, and the two associates are to be ministers.

In Act III, ii, we find further progress of the conspiracy. The conspiracy is disturbed at first by the quarrel between Trinculo and Caliban, and the hand-to-hand fight between Stephano and Trinculo, provoked by Ariel‘s unseen interference. Peace is at last established, and the details of the plot are laid down, the three joining hands in the pledge of the fulfillment of the plot, while Stephano sings ‘a drinking song’, jestingly named by Prof. Dowden “The Marseillaise of the enchanted island”.

In Act V, Prospero foils the conspiracy with the help of Ariel. Caliban and his associates approach the cell of Prospero, intent on his murder. Ariel has already decoyed the three into a filthy-mantled pool. Prospero orders Ariel to bring out trumpery from the cell and hang it on the lime-tree as a decoy to catch the thieves. As Stephano and Trinculo enter the cell, they are charmed by the finery and forget their original purpose. Meanwhile, Prospero sets upon them a band of spirits who, in the shape of hunting dogs, pinch and hunt them. Thus, the drunken conspiracy is brought to nothing.

This conspiracy of the drunken associates against Prospero’s life constitutes a grotesque parody of the more serious conspiracy against Alonso hatched by Antonio and Sebastian. It is ridiculous and provides a good deal of mirth to the audience of the play, Caliban worshipping the wine bottle, the drunken butler, and the jester imagining themselves as king and viceroy of the island. Ariel’s impish trick, which leads to the quarrel between the two conspirators, and lastly the ambitious overlords decoyed by a robe -all these are rich food for laughter. But it has been rightly observed by Boas that “Shakespeare’s humorous genius does not show here to full advantage. The buffoonery of Stephano and Trinculo has a large element of mere horse-play and even the earliest comedies scarcely contain passages of such wire-drawn, insipid repartee as make up the main part of Act II, ii.”

Again, the tricks of Ariel to set Caliban against Trinculo are but the repetition of the tricks of Puck, that impish spirit in the earlier comedy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. These are humorous things which are right, enjoyed by the ordinary folk, but of the higher and more refined humor of Shakespeare, which plays like sunshine on ripples in the mature comedies, we have not the faintest suspicion in this play. The humor here is broad, almost descending into horseplay.