Discuss the patriotic notes in W.B.Yeats’s poem ‘Easter 1916’

W.B. Yeats was intimately connected with the freedom movement in Ireland, and he was, as such, in close kinship with a number of Irish political leaders. His political interest was patriotic, and his aim was definitely to emancipate his fatherland from servility to British imperialism.

Yeats’s poetry includes some poems occasioned by his political interests or active association with specific political events, as well as his ardent sympathy for certain political personalities fighting for Irish freedom. Among such poems may be mentioned September 1913, Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen, and Easter 1916. Of course, nowhere is Yeats’s poetical art lost in any political propaganda.

His poem Easter 1916 appears, more than the other two poems, to be a politically inspired work. It is an exclusive commemoration of a momentous situation in the Irish struggle for liberation against the brutal British power. While the other two poems are related to the immediate social and political contexts of the time, “Easter 1916” is, at least partly, a revolutionary song. The poem was written in September 1916, when the poet was staying with Maud Gonne, one of the chief architects and organisers of the Irish freedom movement. The poem records his deep feelings for and spontaneous reaction to the Easter Rising in Dublin, when the Irish Republican Brotherhood occupied the city’s central position under the leadership of Patrick Pearse and James Connolly. Of course, the result was eventually disastrous. The Irish freedom fighters had to surrender to the brute force of Britain. A good many Irish patriots were killed in the confrontation, and several leaders, at least fifteen, were executed after their court martial by the British army.

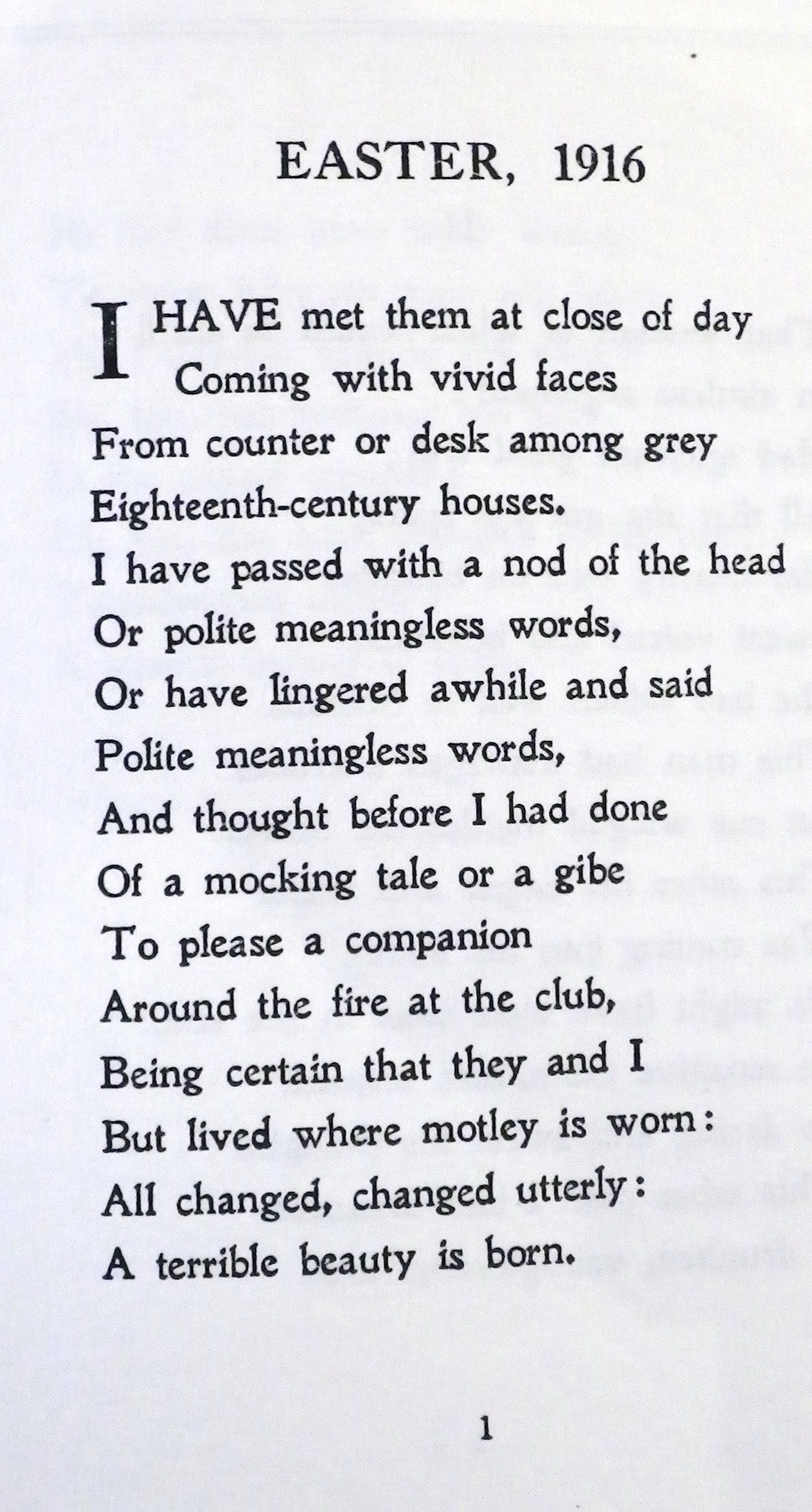

Yeats’s poem is a sort of celebration, with honour and pity, of that memorable event. His poem records, rather feelingly, how the revolutionaries faced their cruel adversaries and remained steady and firm in their cause of liberation. He mentions how those Irish revolutionaries, with their common ways of living and their usual joys and funs, took up arms to liberate their land from oppressive rule. He mentions in the opening stanza of his poem how those unknown patriots came out of their counters and desks in the office, situated in some old buildings. Their faces looked brightened with a happy zeal. They talked at their ease around the fireplace of their club and did not miss a chance to crack jokes and jeers in the course of their easy-going gossip and entertainment.

That was the usual way of living of those Irish men and women who loved their freedom and their land. They came out of their daily drudgery and casual gossip and involved themselves deeply in the grave cause of their land, braving the threat of a mighty force. Of course, the result was terrible. There was the ruthless slaughter of those inspired lovers of their land. Their death was terrible, but it had a deathless beauty in their self-sacrifice. In the poet’s language-“A terrible beauty is born.”

In this context, the poet mentions some of the participants in the 1916 Rising, intimately known to him, such as, Constance Markiewicz, Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, John MacBride, and James Connolly. The first one was one of the leaders of the operation. Patrick Pearse, a poet, was the founder of St. Enda’s School; his friend and helper was Thomas MacDonagh. John MacBright, Maud Gonne’s husband, and James Connolly, a trade union leader, were the leaders and organizers of the Irish revolutionary army. Yeats’s poem refers reverently to them and their great dedication to their country’s cause.

Yeats’s feeling of admiration and profound sympathy for their cause is found echoed in the poem. Out of their routine-bound, dreary way of living, those people remarkably came out and stood together as firm as a stone. Whatever might be monotonous or comical in them had an abrupt change, with the sparks of their glorious end, and the poet unequivocally confirms the same :

Transformed utterly, A terrible beauty is born.

Those persons died, painfully suffering. Yet, their death is not the end of everything. No doubt disaster wiped them all. Their English foes, with their imperialistic faith, might question the necessity of their death. Yet, in Yeats’s line, this is no death, for the heroes are not dead. They live in the dream of those who love their land and form the very material of their song. Their sacrifice is too great, too long, to be cast aside. It is to be acknowledged as solid and permanent. Yeats’s conclusion is agog with his unequivocal admission of their timeless existence in the heart of Ireland :

I write it out in a verse-

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Whereever green is worn,

Are changed, changed-utterly !

A terrible beauty is born.